Why the nuclear debate must uplift women’s voices

Joe Jukes from CND Peace Education discusses women's involvement and explores why justice is central to the nuclear debate.

The question of nuclear arms is stuck in a rut. As recently as the 2019 General Election campaign, any budding prime minister had to be prepared to be asked whether they would press the hypothetical nuclear button. The vast majority of party leaders affirmed their readiness to use nuclear weapons, and those who would not do so were quickly labelled as unelectable, or without backbone. In effect, the question of using nuclear weapons has ceased to be a question – it's been reduced to a litmus test: are you 'man' enough, or not, to hold the lives of hundreds of millions people in your nuclear-armed hands?

The nuclear button has long symbolised collective fears and anxieties. We fear the consequences following an enemy pushing it, and yet are reassured by our leaders' willingness to do just that. The machismo of this willingness is normalised as 'statesmanship'; aggression and warmongering as electability; fear as security.

What happens when we deliberately look at nuclear issues with women in frame?

Setsuko Thurlow and the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons

Born in Hiroshima, Setsuko Thurlow was just 13 when the 'Little Boy' bomb exploded over her city. Now a leading figure in the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN), Setsuko shares her own experience as Hibakusha (a survivor of the atomic bombings). This perspective was instrumental in negotiations that lead to 122 UN member states passing the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons in 2017, a treaty which has made nuclear weapons illegal under international law since 22 January 2021.

The negotiations featured high numbers of women delegates, with several women-only delegations. Elayne Whyte Gómez, who presided over the negotiations said this brought "the ability to receive new ideas, refreshing approaches, and [an] environment that tends to build bridges and to have an atmosphere of trust and hope".

Setsuko accepted the 2017 Nobel Peace Prize on behalf of ICAN, along with its Director, Beatrice Fihn, who sees the treaty as an anti-patriarchal intervention. "For too long, we have left foreign policy to a small number of men, and look where it has gotten us… The survival of the human species depends on women wresting power from men."

Women are disproportionately subject to the harms of radiation exposure as men (PDF); Hibakusha women for example had nearly double the risk of developing and dying from cancers than male atomic bomb survivors. By centring the humanitarian and unequal impacts of nuclear weapons, ICAN made the case for a complete nuclear weapons ban. The Women's International League for Peace and Freedom (WILPF) praised the Treaty for being "the only gender-sensitive nuclear weapons agreement in existence".

By contrast, 2019 saw the tearing up of the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) treaty by both Donald Trump and Vladimir Putin, which outlawed a whole class of nuclear weapons. 2020 saw the US withdraw from the Iran nuclear deal amid nuclear suspicions. And Kim Jong-Un and Donald Trump's disarmament talks thrice failed to yield any real consequences for disarmament and peace. Ditching deal-making and breaking in favour of bridge-building and co-operation not only re-frames the nuclear question, but is actually better at answering it.

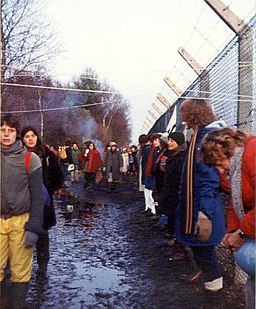

The Women of Greenham Common

In 1981, a group called Women for Life on Earth arrived at RAF Greenham Common to protest US Cruise missiles, due to be stationed on UK soil. These women occupied, blockaded and disrupted the military base for the next 19 years.

In varying number, peaking with a demo of 50,000 women in December 1983, the Greenham women acted for peace and against the patriarchy, aggression and imperialism that, for them, the missiles represented. In their diversity, whether of faith, colour, sexuality, punk, vegetarian, disabled, single, married, old or young, women's liberation and nuclear disarmament intertwined in this and many other peace camps.

One Greenham woman, and director of the Acronym Institute, Rebecca Johnson explains that, "Greenham women insisted that everyone has the power and responsibility to connect with each other and change the world. That was the symbolism of the spiderwebs we wore as earrings and wove across the gates of the base".

Greenham re-framed the nuclear issue, and it lead to the signing of the INF treaty – yes, the one torn up by Trump and Putin in February 2019. It put women at the forefront of peace issues, showing us that when other voices are centred, new ways to peace are unfurled, ways that are less entangled in the usual trappings of patriarchy, colonialism and environmental disregard.

Beyond just women at the table

These stories motivate us to ask more than simply who has the power to push the red button (or not). Such leaders tend to be unrepresentative of those affected by nuclear weapons' impacts. If women can so demonstrably change the nuclear debate, so too can stories of nuclear colonialism transform how we approach disarmament, turning it from a question of security to a question of justice.

The inhabitants of the Marshall Islands lived through over a decade of US nuclear testing. The Marshallese people witnessed nuclear explosions, some as powerful as 1,000 Hiroshima bombs, and have lived with the effects of these tests for over 70 years.

They continue to seek justice from the United States, but were denied the opportunity to mount a lawsuit. Meanwhile, the low lying Pacific islands are highly vulnerable to climate change, not least because of the radioactive waste stored on them.

Kathy Jetñil-Kijiner's poetry and performance makes clear the dual threats of climate change and toxic nuclear legacies. Her work reaches across the world, connecting the experiences of communities as far as Greenland with her own Marshall Islands.

By lifting up the voices of those impacted by and marginalised because of nuclear weapons, the nuclear issue is made more representative and understood in a more intersectional register. Awareness of the structural inequalities that are maintained by nuclear weapons makes the issue more urgent. It is the same question of combatting the violences of toxic masculinity, imperialism, racism and ecocide.

That's why the nuclear debate must uplift women and decentre men.