Stripping back the structure

Do Quaker ways of working stifle the spirit or allow it to speak? Do they welcome or exclude? For the faith to flourish in these turbulent times, perhaps it's time to take a step back and redefine our processes and structures, says Alistair Fuller.

When someone visits a Quaker meeting for the first time, how do they know it is a Quaker meeting? What might they see that would tell them who we are?

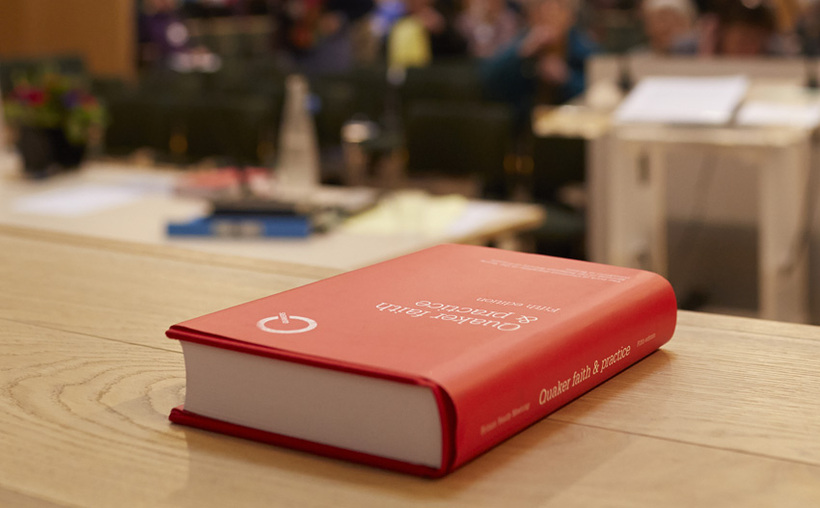

As Quakers we have customs, processes and ways of worship that have endured for centuries. They are quickly recognisable and give shape and substance to our own spiritual lives and our lives as a community. These are the things that many people encounter once they have attended their first meeting and are beginning to look more deeply into what it means to be a Quaker.

Many of us are deeply familiar with these structures and indeed can find great comfort and reassurance in them. But might there also be something about the shape and structure of our Quaker communities – locally and nationally – that makes them difficult to access for many people?

Is there sometimes something about our ways of working that seems to stifle the Spirit, rather than creating the space for it to flourish and speak?

Serving the structure?

I think it's fair to say that while for many of us finding Quakers feels like coming home, there are others for whom it feels like anything but.

There are many to whom the truths and challenges of the Quaker way might speak powerfully, and who would find deep nourishment in our worship. Yet they feel little sense of welcome or belonging in the Quakerism they find.

Quaker community and the structures within it can often be experienced as excluding, exclusive and difficult to access; they can contain all kinds of unacknowledged hierarchies and unspoken assumptions. It is all too easy to find ourselves serving the structure rather than allowing the structure to serve the Spirit.

Define and redefine

A question I have found myself asking again and again over the past years may help us with this challenge. It is: if we strip away the language and custom and familiar structures of Quakerism, what are the bare bones that would be left? What lies at the very heart of what it means to be a Quaker community?

This is not a new question. In 1984 Alison Oldham spoke at New England Yearly Meeting:

“If we accept the notion, however subconsciously, that Quakerism really speaks only to certain kinds of people, then it seems to me we have totally denied its religious validity, its universal spirit, and have reduced Quakerism to the status of a social club with a mild religious overlay.

It's an ongoing task, I believe, of every religious faith, from time to time, to define and redefine itself, to identify which of its traditions are essential and irreducible, and which are mere trappings – cultural baggage that can be discarded when no longer helpful."

An adventurous future

These are challenging statements – I imagine that for everyone who finds our processes alienating there is someone who takes comfort in them.

But if we dare to ask these questions, to look beyond our present processes and structure and reach to the core of our faith – what might our Quaker communities be like then? Might they become places of greater openness and welcome, more richly diverse and more genuinely equal? Places of transformation, inspiration and radical, Spirit-led action?

Of course, there are no guarantees or magic solutions. Any kind of community is made up of flawed and faulty human beings, with different needs, burdens, gifts and stories; we inevitably and invariably make mistakes and get it wrong.

Yet it seems to me that Quakerism is, in its very nature, adventurous, bold and creative. Back in the 1650s those first seekers were led by a transforming experience of God, to create a new community of faith, uncluttered by habit and tradition; a community in which the Spirit was free to flourish and speak and from which women and men might be sent out to work for the transformation of the world. It was a challenging and difficult process for them, just as it might be for us today.

Remembering those early Friends leads us to ask: if they were forming a new and radical religious society today, what might it look like? And how might we, as their successors, begin to imagine and shape a Quaker community that is as full of freedom, promise and purpose as it needs to be in these turbulent times?

![close up of Holocaust Memorial Garden stone, Hyde Park, London. Inscription reads: Holocaust Memorial Garden ה'כךנ 'נא הלא לע 'נ'ע ךךה ם'מ 'נלכ 'מע תב ךנש לט [אבה] For these I weep streams of tears flow from my eyes because of the destruction of my people. (Lamentations)](/media/W1siZiIsIjIwMTgvMDEvMjYvMTEvNTEvNDEvYmNmZTZmM2QtZjJkNS00MjEzLTk5ODctNTk5ZjBkOGJhMTIwL1JhY2tNdWx0aXBhcnQyMDE4MDEyNi05NzE1LTFyN3F2ZWcuanBnIl0sWyJwIiwidGh1bWIiLCI0MTl4MjMzIyJdXQ)