George Fox 400: Expanding the narrative

Ellie McCarthy examines the part George Fox played in Quaker attitudes towards enslavement.

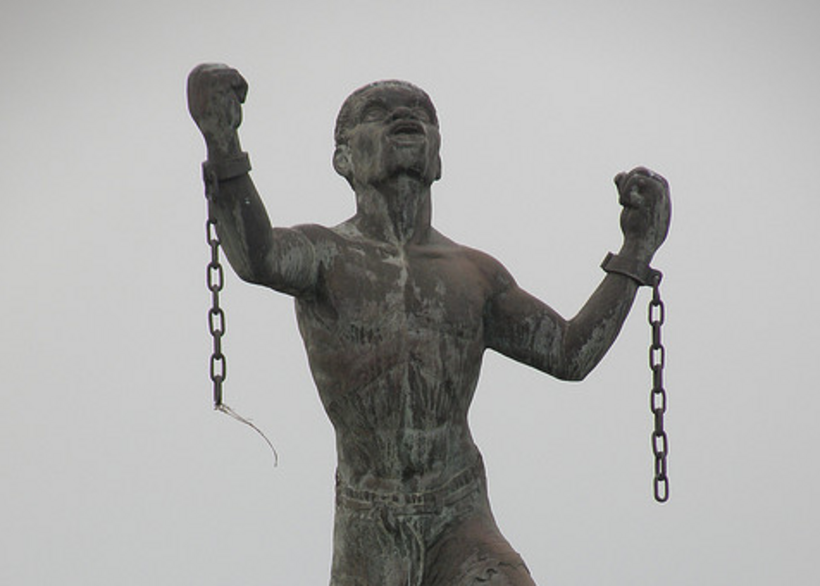

Since the murder of George Floyd in 2020 and the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement, many organisations in Britain have been re-evaluating their history, searching for the roots of the systemic racism which surrounds us today.

This involves recognising systemic racism in current organisations, so it can be tackled, but also identifying historic links to the transatlantic chattel slave system and associated African ethnocide, which resulted in monetary and other assets.

Quakers in Britain is part of this groundswell of change – in 2022, British Quakers committed to making meaningful reparations for the transatlantic slave trade, colonialism and economic exploitation.

Identifying links between early Friends (as Quakers call each other) and the transatlantic chattel slave trade is a key step towards making meaningful reparations. So, when the 400th anniversary of George Fox's birth came round this year, it was necessary not only to celebrate his life, but also to examine the part he played in Quaker attitudes towards enslavement.

Early Quakers and slavery

George Fox is an influential figure in Quakerism. He played a major role in the formation and expansion of the movement in the mid-1600s, and his experiences and writings still provide inspiration for Quakers across the world today. But some parts of his story are less well known.

When it comes to Quakers and the transatlantic chattel slave trade, most people think of the part they played in abolition. In the 18th century, Quakers became the first organisation to undertake a large-scale anti-slavery campaign. However, the full story of Quakerism's connection with transatlantic trafficking begins a century earlier, with George Fox and other early Friends.

In 1671, a group of Quakers sailed from England to Barbados. This was George Fox's first visit to the 'New World'. The group stayed with various Quakers, some of them rich landowners who owned hundreds of enslaved people.

One was Thomas Rous, father of John Rous who had married Margaret Fell's oldest daughter. Oranges and sugar, grown through the forced labour of enslaved people on the Rous plantation, were sent to Swarthmoor Hall, home of Margaret Fell and an early centre of the Quaker movement.

The role of George Fox

The interactions George Fox and other Friends had with enslaved people in Barbados were unusual for the time. Black people were invited to meetings for worship on the plantations and Quakers were encouraged to treat the people they had enslaved kindly. Fox also suggested owners set them free after thirty years' service. How the enslaved people who met with this group of early Quakers felt about these interactions is unknown.

But while he advocated for kind treatment and a religious life for the enslaved, George Fox did not stand against slavery. In a letter to the governor of Barbados he made clear that Quakers were not inciting enslaved people to rebel. Instead, he argued, they urged Black people on the island to act piously and "be subject to their masters and governors".

Faced with the horrendous reality of the transatlantic slave trade in action, Fox and other early Friends chose not to condemn the practice.

This lenient attitude paved the way for Quaker businesses to expand through wealth created using unpaid forced labour of enslaved people. Some of this wealth flowed into wider Quaker circles, contributing to the building of meeting houses and other assets.

Direct Quaker involvement in the transatlantic trafficking of enslaved people also strengthened the racist attitudes and systems of the 17th century that underpinned many aspects of British life. That systemic racism is still clearly visible in Britain and around the world today.

Working towards reparations

Two years after committing to making meaningful reparations for the slave trade, colonialism and economic exploitation, in the anniversary year of George Fox's birth, more Quaker communities across Britain are researching Friends' historical links with slavery.

Connections are being made with other faith groups advocating for reparations, like the Church Reparation Action Forum of Jamaica. The Quakers in Britain Reparations Working Group advises on practical contributions, including offering rooms at Friends House, the central offices of Quakers in Britain, for reparations-focused events.

These are first steps towards making practical reparations. By expanding the story of historic Quaker involvement in these practices, we are better placed to work towards a brighter future.