Peace is the best medicine

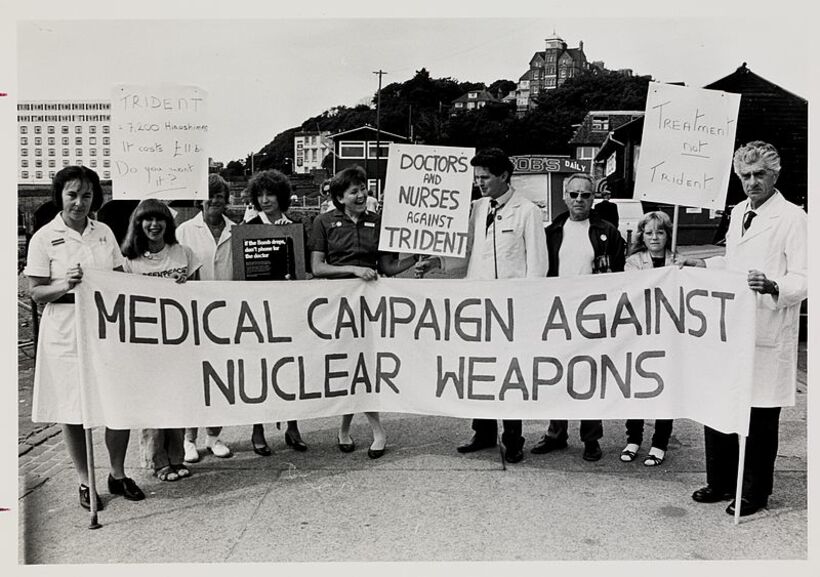

Medical doctor Martin Hartog describes his role in the formation of MEDACT's antecedent, the Medical Campaign Against Nuclear Weapons (MCANW).

In 1979, Claire Ryle from Cambridge was instrumental in inviting Helen Caldicott, a paediatrician from Australia, and a passionate anti-nuclear weapon campaigner, to speak in the UK. One upshot of this was the convening of a meeting at University College London to discuss setting up a medical anti-nuclear weapon organisation in the UK. I attended, with two colleagues from Bristol, and was delighted, but not surprised, to find the meeting chaired by somebody who had supervised my efforts at research, John Humphrey, a charismatic immunologist. The decision was made to set up such an organisation, with John as chair, but, interestingly, and I believe correctly at the time, not to include nuclear power as a target for campaigning.

Medical Campaign Against Nuclear Weapons

At a subsequent, similarly inspiring, meeting, the decision was made to call the new organisation the Medical Campaign Against Nuclear Weapons (MCANW), which became the UK affiliate of the International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War (IPPNW), the latter organisation being later awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1985. MCANW was open to all health care professionals and grew to a membership of about 3,000 but this dropped off in the late 80s.

Becoming more involved

[QUOTE-START]

You make a living by what you get, but make a life by what you give.

[QUOTE-END]

Curiously, given that I had no sort of background to political activity, and my medical knowledge had nothing to do with the medical effects of nuclear weapons, I became heavily involved in campaigning. After a day's work, I would drive quite far afield, sometimes with my wife Sally, to talk about their medical effects, arguing for the total abolition of such weapons with health care professionals and peace groups. Several of these meetings were characterised by polite, but quite outspoken, criticism of my support for nuclear disarmament by health care professionals in the audience!

On the principle that, if you want to learn about a subject, teach it, I did quite a lot of homework on the gruesome issues involved. In 1982 I, together with John Humphrey and another colleague, Hugh Middleton, published a booklet The Medical Consequences of Nuclear Weapons. The booklet proved useful at the time but was later overshadowed by a much more authoritative book from the British Medical Association's Board of Science.

After a few years, John Humphrey's increasing deafness made him have to give up as chair and I succeeded him for several years. One event that I particularly remember was a break-in to our headquarters, then near Waterloo Station, and, rather disturbingly, a theft confined to our membership records. I remember also Bill Hoffenberg, our president at the time, ringing me to tell me of similar, and much more serious, events with which he was involved in South Africa before he came to England in view of his outspoken opposition to apartheid. He advised that we should not be too worried about the theft and, in fact, nothing that we could detect seemed to come from it.

Another memory was of a return visit by members of the IPPNW from Tbilisi, Georgia, with which Bristol is twinned, which finished with a very joyous occasion in our house with about twenty people at which the wine flowed, there were numerous toasts, and we were presented, perhaps rather curiously, with a Sword of Peace.

In 1992, MCANW joined with the Medical Association for the Prevention of War (MAPW), a medical peace organisation of much longer standing, to form the Medical Action for Global Security, this name being subsequently shortened to Medact, which is now a well known, more general environmental organisation, concerned with matters of peace and health but which has not, in any way, lost its concern about nuclear weapons.

An egalitarian organisation

Although I did not realise it then, becoming involved with MCANW was very good for me in exposing me to what was very much an egalitarian organisation, as compared with the then rather hierarchical NHS, in which everyone felt free to speak his/her mind. No one was in it for personal gain but rather for mutual support.

Another consideration that I have had, in retrospect, is how my involvement with MCANW partly paralleled my deepening interest in Quakerism, having started going regularly to Meeting shortly after we came to Bristol in 1969. Being a Quaker has meant a huge amount to me. As felt by so many others, it is the lack of dogma, the constant seeking, the concept of 'that of God in everyone', the recognition that each of us is on an individual spiritual journey and the active social witness, that are so impressive.

As a rather remarkable chimney sweep once said to me “We make a living by what we get, but we make a life by what we give"*.

* Words that have been attributed to Winston Churchill but, apparently, incorrectly.