Sowing seeds for a Quaker new economy

A Quaker entrepreneur has turned his hand to mustard-making. Olivia Hanks looks at how the business is part of a new economy informed by Quaker ethics.

In 2015, dozens of Quakers from around the country contributed to the creation of 10 principles for an new economy rooted in Quaker values of equality, truth, simplicity and peace.

Since then, more than 60 local reading groups have formed to discuss aspects of the economy with the help of a series of booklets we produced.

But what does 'building the new economy' mean in practice? It might sound a bit abstract, but in fact many Friends are already involved in local initiatives that put the principles into practice, from community gardens to repair workshops.

At the heart of the new economy is the principle that economic activity should boost wellbeing, not just profit margins. In the dominant economic system, public limited companies trade their shares in the market. Those who buy shares and own a publicly-traded company usually have no interest in it beyond what it can earn for them. Disregard for the wellbeing of people, nature and communities is built into this economic model.

The unhappiness that this economy creates has led to the growth of cooperatives and a wider 'social economy' – a collective term for organisations which exist to pursue goals other than private profit.

Owned by their workers, residents or customers, cooperatives are a highly democratic form of business ownership, run on seven core principles: open membership, democratic member control, member economic participation, autonomy, education, cooperation among cooperatives, and concern for communities. Various studies have found them to be more resilient than privately-owned businesses in times of economic crisis.

So what role are Quakers playing in this growing movement for change?

Case study: Norwich Mustard

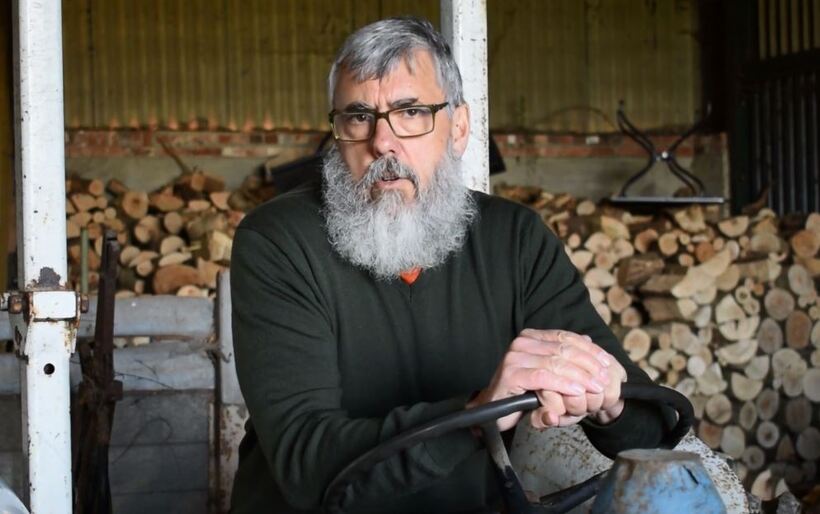

Norwich Quaker and entrepreneur Robert Ashton has long been a fan of cooperatives. When it was announced last year that iconic Norwich mustard firm Colman's – which was bought by Unilever in 1995 – would be moving production out of the city, he decided to act.

"Norwich people were angry and upset about Colman's closing," he says, "so I decided to do something to convert that anger into positive action."

Along with a local councillor, Robert founded Norwich Mustard, in order to keep mustard production in Norwich after Colman's leave.

A crowdfunding campaign to fund the start-up was supported by 184 people, many of whom posted messages of support. "What a great idea. I fully support keeping mustard production in Norwich as part of our heritage," wrote one supporter. Another explained: "As Bracondale residents who live in a house once owned by Colman's we well appreciate the heritage of this industry in the city. Good luck with your enterprise."

Norwich Mustard is a community benefit society, which means that every shareholder will have equal say, however many shares they own. A pilot run was outsourced and test-marketed at retailer House of Fraser in July, and more than 250 jars were sold. A community share issue is planned for the autumn, allowing supporters of the enterprise to become co-owners.

The first jars of Norwich Mustard carry a picture of Elizabeth Fry – another Norwich Quaker, best remembered for her work as a prison reformer. And this is no coincidence, as Robert explains.

"Norwich Mustard will be produced inside Norwich Prison, providing valuable pre-release work experience to prisoners nearing the end of their sentence. There's a stack of evidence that this reduces the risk of re-offending and I'm all for helping those others would prefer to forget."

A taste of the future

Next year should see Norwich Mustard open a mustard heritage centre in a disused city centre church. Here visitors will be able to see how mustard is made, learn about the history of mustard making in Norwich, and taste the product in a themed café.

Robert says that while Norwich Mustard is not officially a Quaker enterprise, "it is very much managed with the testimonies in mind. Collective ownership provides a very real alternative to the corporate structures that prevailed in the 20th century and there is a real resonance between cooperative principles and Quaker testimonies.

"I'm determined to make Norwich Mustard simple, honest, equal – and to focus public anger into something more constructive than knocking Unilever."